Why Psychoanalysis Is More Relevant Than Ever

The recent revival of Psychoanalytic Therapy shows that we must question the dominant idea that reduces psychic organisation to faulty cognitive processes or to the determinism of neurochemistry.

Psychoanalytic theories seek to understand a person's unique phenomenology. This approach honors and supports the meaning and values that give significance to our human lives.

In the modern age of neuroscience, a person's experience of life is sometimes reduced to a discussion of biochemistry and brain structures. Love, happiness, sadness, or unhappiness can seemingly be easily "explained" by observing specific brain regions, and the action of neurotransmitters.

While remarkable advances in science have enabled researchers to understand how biological systems function when emotions are experienced, they offer descriptions of how they occur, not explanations of the underlying phenomena.

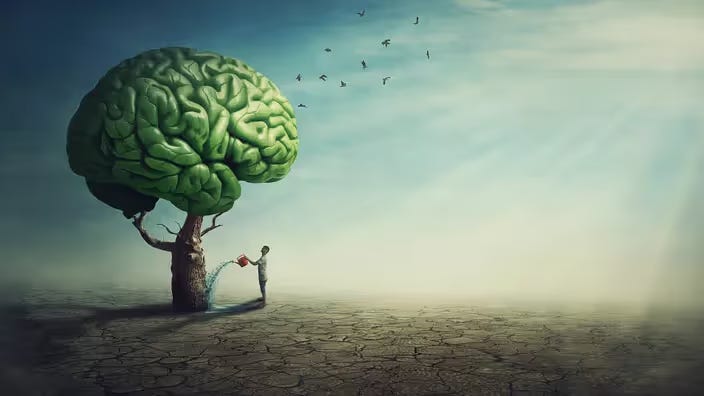

By reducing the essence of human experience to an objectified, deterministic, and mechanistic system, we deny the most important of human capacities - our imagination! Our ability to create seemingly limitless ideas and stories has allowed the mind to emancipate itself from the constraints of sensory reality. We imagine, invent, create, and transcend the material world into a world of possibilities.

All civilized societies require people to conform to the norms, rules, and expectations necessary to live cooperatively. Our socialization begins at birth and requires that a person learn to adapt to social demands and internalize them as if they were their own. The main task of mental health is to achieve this conformity while preserving personal integrity despite a fragmented self. This integrity requires us to respect our diversity in many forms, such as ethnicity, religion, sexuality, etc., while balancing our needs for social connection and acceptance. Psychoanalytic therapies have kept these existential considerations central to the mission of advancing human understanding and promoting personal fulfillment.

Today's technology allows us to satisfy many of our needs almost immediately, but this convenience can undermine a person's emotional maturity by bypassing their ability to tolerate frustration. It involves the ability to delay gratification, contain states of tension, inhibit reflex actions, and engage in thoughtful planning. In the absence of this ability, we are inclined to adopt impulsive and potentially addictive lifestyles. It's not surprising, then, that these lifestyles have historically been seen as characteristic of adolescence, when brain development is still immature. But when needs and demands can be met in nanoseconds, there's little incentive to cultivate self-control.

Psychoanalytic therapies aim to improve self-awareness. Patients are encouraged to seek their personal truths through introspection and insight. The therapist's role is that of a guide who accompanies patients in exploring and examining their innermost mind and questioning the narrative of their identity. As a guide, the analyst offers protection against the fear of self-knowledge and, more importantly, serves as a witness to personal truths that may need to be proclaimed. Guiding and witnessing are among the most important interpersonal functions, providing safe acceptance and validation of the individual. These functions create the conditions for healthy attachment and honor a person's worth and purpose.

As a system for understanding mental illness or human suffering, psychoanalytic models offer a compassionate and normalizing perspective. If symptoms are an expression of suffering, they also represent a person's best efforts to maintain their sanity, whatever that may be. Neuroses are distinguished from other forms of distress by referring to psychological suffering arising from conflicts within and between people. The gift of imagination can also be a curse when it comes to confronting unfathomable thoughts, fantasies, and memories. Psychoanalytic therapy enables the patient to distinguish perceptions from fantasies, desires from needs, and speculations from truths. Understanding and correcting emotional experiences with the therapist can help a person regain his ability to care for himself and for loved ones.

Why do critics of psychoanalysis claim that it is not a science and does not stand up to rigorous empirical validation through scientific testing? This criticism is misleading. In psychoanalytic therapy, treatment focuses exclusively on a person's unique subjective experience. Consequently, each therapy is tailored to the specific needs of the individual, according to their personality, experience, skills, and maturity. One person's therapy cannot be accurately compared to another's, which precludes the meaningful comparisons needed for scientifically controlled research studies. In other words, psychoanalytic therapies treat people, not symptoms.

The analytic approach to psychotherapy values the person over the diagnosis. This may be achieved by reducing symptoms to some extent, but it may also involve accepting oneself and the fact that certain life problems need to be overcome rather than "solved".

In addition, numerous studies have shown that the most important factor in successful psychotherapy of any kind is the quality of the relationship between therapist and patient. The therapeutic relationship—or alliance—has been the cornerstone of psychoanalysis since its inception. The quality of that relationship cannot be quantified objectively.

Nobel laureate Eric Kandel has stated that psychoanalytic theory offers the most complete understanding of the mind of any psychological theory. Its ideas and concepts have undergone over a century of revision and modification to help us understand the human condition.

As complex, multifaceted creatures, we are endowed with relentless curiosity and remarkable resilience. We invented not only science but also the humanities. Art, music, literature, and philosophy are methods humans have created to express the immensity of our shared life and the desire to understand the essential meaning of our existence. Psychoanalytic theories also explore our relationship to these human sciences as they can have personal meaning for the individual.

Psychoanalysis grew out of Freud's desire to understand himself and others as members of a dominant global species. All of our modes of expression serve to approach, but never fully elucidate, human uniqueness. The Freudian subject is a free subject, endowed with reason, but whose reason wavers within itself. It is from their words and deeds, and not from their alienated conscience, that the horizon of their own healing can emerge.

This subject is neither the automaton of the psychologist, nor the cerebro-spinal individual of the physiologist, nor the somnambulist of the hypnotist, nor the ethnic animal of the theorist of race and heredity. They are a speaking being, capable of analyzing the meaning of their dreams, rather than seeing them as the trace of a genetic memory or a set of neurons. Their limits are undoubtedly determined by physiology, chemistry, or biology, but also by an unconscious that is conceived in terms of universality and singularity.