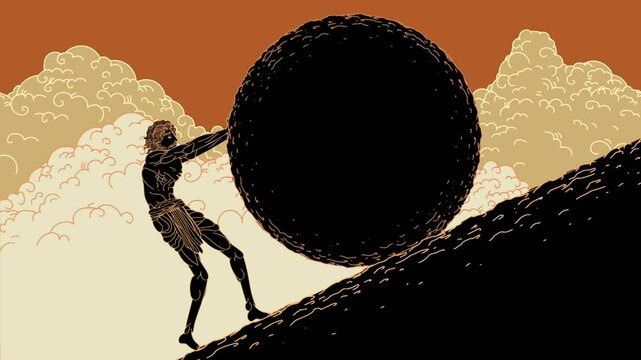

The Effort-Avoidance Bias: When Choosing Comfort Makes Your Life Smaller

Why laziness, procrastination, and avoidance are the same psychological mechanism—and how deliberately seeking friction rewires your brain from protection mode to growth mode

Your brain is not your ally in becoming the person you want to be. It’s a deeply conservative institution, more concerned with preserving yesterday’s status quo than building tomorrow’s possibilities. And it has a preferred method for doing this—one so subtle you probably mistake it for a personality trait.

I call it the effort-avoidance bias, and it’s running more of your life than you think, with dramatic consequences.

Modern culture has become an elaborate conspiracy to reinforce this bias. Everywhere you turn, someone is selling the promise that good choices should be easy, risk-free, and painless. Education markets itself as “engaging” and “fun” rather than challenging. Capitalism has discovered that the most profitable product isn’t excellence—it’s the illusion of excellence without effort. Quick recipes. Self-help shortcuts. Wellness placebos. We’ve built an entire economy around the idea that discomfort is a design flaw to be engineered away rather than a signal pointing toward growth.

We over-coddle children, removing every obstacle before they encounter it, then wonder why they arrive at adulthood unable to tolerate frustration. We buy books promising “effortless transformation” and apps that gamify discipline into dopamine hits. The message is always the same: if it’s hard, you’re doing it wrong. If it requires sustained effort, there must be a hack. If it feels uncomfortable, swipe left and find something easier.

This cultural mythology collides headlong with a fundamental truth: nothing worth developing—not skill, not character, not depth—comes without friction. And so we find ourselves in a peculiar bind, surrounded by tools designed to eliminate resistance, wondering why our lives feel so strangely hollow.

The Conspiracy of Comfort

Let’s start with what seems like three separate problems: laziness, procrastination, and avoidance.

We treat them as distinct character flaws, each requiring its own self-help intervention. But psychologically, they’re the same animal wearing different suits.

The evolutionary mechanism beneath all three is your brain’s attempt to conserve energy and neutralize perceived threat. Think of it as an overprotective parent who never got the memo that you’re no longer a toddler. It sees effort and immediately sounds the alarm: “Too risky. Too costly. Let’s not. Fuck no”.

This made perfect sense when our ancestors were scraping by on uncertain calories. Unnecessary exertion could mean the difference between survival and starvation. But now? That same protective instinct manifests as an internal resistance fighter, sabotaging your attempts to write that proposal, have that difficult conversation, or finally deal with whatever you’ve been “meaning to get to.”

The Brain’s Threat Detection Gone Wild

Anything uncertain, effortful, or emotionally loaded triggers your brain’s danger detector—the amygdala and its avoidance circuitry. This ancient system interprets:

Effort as risk

Discomfort as danger

Challenge as “abort mission”

So when you procrastinate on your taxes or avoid that gym session, you’re not being weak. You’re experiencing a sophisticated threat response originally designed to keep you from wandering into a lion’s den. It’s just that your brain can’t distinguish between actual danger and the discomfort of doing something hard.

Avoidance works—at least in the short term. Dodging the uncomfortable task gives you immediate relief, a micro-dose of “ahh, that’s better.” Your brain, always learning, marks this down as a win. Relief equals reward. And rewards get repeated. The dopamine effect kick in.

Avoidance is a simple way of coping by not having to cope.

You’re not actually managing the situation—you’re just deferring it. The email still needs to be sent. The conversation still needs to happen. The project still sits there, accumulating interest like unpaid debt. And with each deferral, the psychological weight grows heavier while your capacity to handle it atrophies from disuse.

This is how avoidance becomes a habit, then a pattern, then—if you’re not careful—a life that feels increasingly constricted. Each thing you sidestep shrinks your world a little more.

The Counterintuitive Solution: Seek the Friction

The ancient Stoics understood something modern neuroscience is only now confirming. As Seneca wrote: “A gem cannot be polished without friction, nor a man perfected without trials.”

“A gem cannot be polished without friction, nor a man perfected without trials.”—Seneca

The way out isn’t what most self-help literature suggests. You don’t need more motivation, better time management skills, or a productivity app that gamifies your to-do list. You need to fundamentally change your relationship with effort itself and learn to become comfortable with discomfort..

Instead of waiting to feel like doing the hard thing, you deliberately lean toward it. Not because it’s pleasant, but because friction is the only force that rewires the system.

Bones get stronger through mechanical stress; trees grow stronger because of the repeated pressure of the wind; muscles develop only when pushed against a load.

Friction activates growth circuits. The moment you face a challenge, you trigger neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to form new connections. Learning, adaptation, competence, reward—all of these networks light up when you engage with difficulty. Avoidance keeps them dormant.

Action regulates emotion, not the other way around. This is perhaps the most important insight from behavioral psychology: mood follows action, not the other way around. We’ve been taught to wait for the right emotional state before acting. But the research suggests the opposite—doing the hard thing first creates the emotional shift you were waiting for. Suddenly, relief becomes associated with completion rather than escape. That’s what builds motivation.

Small friction inoculates against bigger threats. Think of it like physical training. Lifting weights creates micro-tears in muscle that heal stronger. Facing mild discomfort does the same for your psychological resilience. Each time you lean into resistance—sending that email, having that conversation, doing that workout—you build tolerance, confidence, and a reduced anxiety response to future challenges.

Seeking friction reconditions the instinct itself. Every time you voluntarily engage with difficulty, you’re teaching your brain a new lesson: “Effort is not danger.” Over time, the neural pathways that once triggered avoidance start triggering something else entirely—anticipation, curiosity, even reward.

The Tipping Point

Let’s be honest about how change actually happens. It’s rarely because you woke up one morning feeling inspired or suddenly discovered willpower you didn’t have before.

Change happens when the math shifts.

Once the discomfort of staying the same surpasses the discomfort of change, you take the leap. Not before. Not when you “should.” Not when it’s convenient or when you’ve figured everything out. You move when remaining stuck becomes more painful than the uncertainty of moving forward.

This is why New Year’s resolutions so often fail—they’re based on arbitrary timing rather than genuine readiness. But it’s also why people sometimes make radical changes that surprise everyone around them. The outside world sees sudden transformation. The person living it has been accumulating discomfort for months or years, until the internal pressure finally exceeds the resistance.

The question isn’t whether you’ll reach that tipping point. If you keep avoiding, you will—the accumulating weight of unlived life guarantees it. The question is whether you’ll wait for crisis to force your hand, or whether you’ll start building tolerance for discomfort now, on your own terms.

The Identity Shift

This isn’t just about productivity or accomplishing more. It’s about who you become in the process. And it’s a choice you make.

When you consistently choose friction, you’re not just checking off tasks. You’re building a new narrative about yourself: “I’m someone who does hard things.” This becomes a core piece of your identity, a through-line that connects disparate experiences into a coherent story of capability and growth.

The alternative—the path of least resistance—doesn’t lead to peace. It leads to a life that feels increasingly fragmented and shallow, because you’re constantly at odds with the person you suspect or hope you could be. Each avoided challenge whispers: “You’re not capable of this.” Eventually, you start to believe it.

The Paradox at the Heart of Growth

Avoidance is the psyche’s way of keeping life smooth. Growth requires willingly roughening the path.

You don’t seek friction because it feels good. You seek it because it’s the only lever that shifts your brain from protection mode into expansion mode. From conserving what is, to building what could be.

Your brain’s ancient programming served you well once. But now it’s a relic, a well-intentioned system optimized for a world that no longer exists. The question isn’t whether you’ll face discomfort—you will, either from avoiding what matters or from pursuing it.

The real question is: which kind of discomfort leads somewhere?

The discomfort of avoidance accumulates silently, making your world smaller with each thing you sidestep. The discomfort of engagement—of friction—expands your capacity, your confidence, your sense of what’s possible.

One kind of pain closes doors. The other opens them.

Choose accordingly.

As a former therapist, I agree with a lot of the mechanism described here… and I also want to name where this conversation often goes sideways for women.

Yes, avoidance shrinks your life. Yes, friction builds capacity. But what I see, over and over, is women weaponizing this framework against themselves.

They read something like this and think, I’m lazy. I’m avoiding. I need to push harder. I need more discipline. More friction. More effort. And suddenly growth becomes another performance, another self-improvement project rooted in self-criticism instead of self-leadership.

The nervous system doesn’t only avoid because it’s afraid of effort; it also resists what isn’t true, sustainable, or self-honoring. And women, especially, have been trained to override that signal in the name of grit, resilience, and doing hard things.

There’s a difference between avoiding discomfort because you’re scared and declining discomfort because it costs you your self-trust, your body, or your peace.

The work isn’t “do harder things.” The work is: become the woman who can tell the difference.

Great article thanks Rob. It reminds me of an old Chinese saying: bitter practices can make for a sweet life