Succeeding at Failure: Why Getting it Wrong is How You Get it Right

Most people get failure wrong—they either ignore it or let it define them. Here's how to fail productively, extract the lessons, and actually grow from your mistakes.

“Success is failure in progress.” There’s a quote commonly attributed to Albert Einstein that most people get backward: Not failure leads to success. Not failure can become success. Failure is success. Like many Einstein quotes, this one appears to be apocryphal. In a cryptic way, it captures the Stoic idea of growth.

The most fascinating thing about failure is how we treat it as if it were contagious. As if dwelling on it might result in something terminal. So, we either pretend failures never happened—denying or forgiving and forgetting—or we turn them into scarring events that define us forever. Silicon Valley celebrates failure rhetorically, but punishes it selectively and remembers it strategically. Blame, shame, and never let anyone forget it.

Neither approach works. And both miss Einstein’s point entirely.

The Identity Problem

Most of us get stuck because we can’t separate the act from the actor. You make a mistake, and suddenly you’re not someone who did something wrong, you’re someone who is wrong. The failure becomes you. It colonizes your identity.

This is where shame does its damage, and it’s a fundamental cognitive error. When we’ve invested our reputation, our time, our money into something, our ego is on the line. So when things go wrong, our brain does a neat little trick; it fuses the mistake with our identity. “I failed” becomes “I am a failure.”

Once that happens, progress stops. Because if the mistake is who you are rather than what you did, there’s nothing to build on. You’re standing on quicksand, and you’re gonna keep sinking. There’s only something to hide from. And you can’t make progress while you’re hiding.

Fail Fast (But Know the Difference)

If you’re going to fail—and you will—then fail quickly enough so that you don’t end up further in the ditch or in debt. But don’t fail so fast that you give up too early. This isn’t just startup wisdom. It’s psychological common sense.

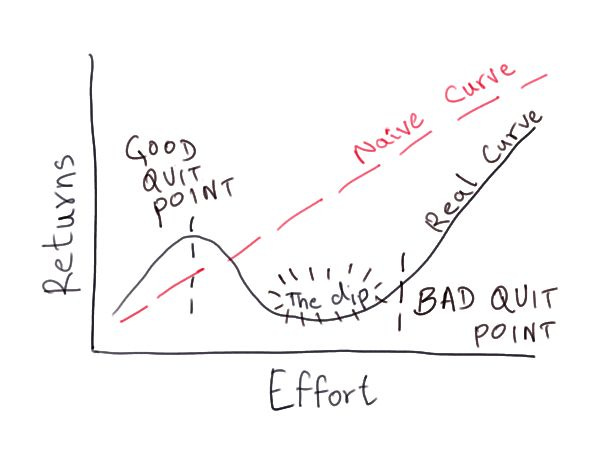

In one of his less-known books, marketing guru Seth Godin talks about “The Dip”—that brutal middle stretch between starting something and mastering it, when everything gets harder before it gets better. Most people quit during that stage. In reality, some dips are worth pushing through, while others are dead ends dressed up as challenges.

Failing fast means getting feedback early, when the stakes are still low, and you haven’t mortgaged your identity to the outcome. It means running micro-experiments instead of betting the house on a single approach. It means asking for an honest assessment before you’re too invested to hear it.

The longer you wait to fail, the more expensive it gets—not just financially, but psychologically. You’ve sunk more time, more ego, more money into that thing. And that makes it exponentially harder to throw the towel and extract any useful learning from the wreckage.

Quick failures give you information when you can still use it. Slow failures give you scar tissue and regret.

But—and this matters—failing fast isn’t the same as quitting at the first sign of difficulty. If you’re in a real Dip, the kind that separates people who achieve extraordinary things from people who dabble, you need to push through that stage. The trick is knowing the difference between a Dip (hard but high potential payoff if you push through) and a Dead End (hard and gets you nowhere).

You know the difference by paying attention. By the feedback you get, and also by your gut instinct. A Dip shows incremental progress, even if it’s grinding. A Dead End shows you the same failure pattern repeating with minor variations. One is teaching you something. The other is just pulling you down.

The Forgive and Remember Framework.

The organizations that actually learn from failure—and there’s solid research on this from hospital systems that study medical errors—use what I call the “forgive and remember” approach.

Forgive, because without psychological safety, people won’t admit mistakes. They’ll cover them up, minimize them, and blame someone else. The whole system becomes defensive and opaque. No one makes progress because no one’s being honest about what actually happened.

Remember, because amnesia is just another form of waste. If you’re going to pay the price of a failure—and you’ve already paid it—you might as well get your money’s worth by extracting the lesson. This is how failure becomes progress rather than just damage.

This is harder than it sounds. Forgiving requires you to separate the person from the behavior. Remembering requires you to stay with the discomfort long enough to understand what went wrong and why. Most people would rather do neither.

What Edison Understood About Failure

Everyone knows the Thomas Edison story. He filed (and was granted) a total of 1,093 U.S. patents during his lifetime. Made a thousand failed attempts at the battery, and when confronted, he reframes them: “I haven’t failed a thousand times. I’ve succeeded in showing what doesn’t work a thousand times.”

Edison understood what Einstein was articulating. Those thousand failures were the success. They weren’t steps toward success or obstacles to overcome. They were the actual substance of the achievement. Each failed experiment was progress—messy, expensive, frustrating progress, but progress nonetheless.

Edison failed fast. He conducted rapid experiments, collected data, learned from his mistakes, and moved on. He was ruthlessly efficient about identifying what didn’t work so that he could focus on what did.

This is the psychological move that separates people who fail productively from people who get crushed by failure: the ability to see failure as material you’re working with, not evidence of your inadequacy.

Indefinite vs Definite Optimism

In his book Zero to One, entrepreneur and investor Peter Thiel outlines two contrasting philosophies for approaching entrepreneurship.

Indefinite optimism is believing that the future will be better, despite having no particular plan for how to achieve it. That’s the lean model. You just keep trying things—meetings, experiments, pivots, and iterations—until something works by accident. Failure becomes necessary because you have no clear idea of what success looks like. It’s like running a Darwinian trial-and-error experiment until evolution does its thing.

On the other hand, definite optimism is believing that the future will be better and having a concrete plan to make it so. Take the Golden Gate Bridge, for example. The Manhattan Project. These weren’t stumbled upon through happy accidents or trial and error. Definite optimism is not an effective way to plan and avoid failure. It doesn’t mean avoiding failure; it means managing it. The Golden Gate Bridge required countless failures. Failed prototypes. Collapsed test structures. Materials that buckled under stress. But those weren’t random failures. They were systematic experiments with clear hypotheses about what needed to work and why. The engineers knew which failures would be informative and which would be catastrophic. They conducted controlled experiments, learned from the results, and advanced with more knowledge. The failures had purpose.

Intentionality is what separates productive failure from aimless flailing. You need a hypothesis, even if it turns out to be incorrect. You need to know what you’re testing and what you’ll learn from each attempt. Otherwise, you’re just amassing random failures without extracting their value.

The indefinite optimism that characterizes so many startups is problematic. It’s not that people are trying things and failing; it’s that they’re failing without learning from their mistakes. They’re pivoting without understanding why. They mistake activity for progress. They hope that if they just keep moving, something good will emerge from chaos. But hubris isn’t a strategy.

The Four Things You Need

If you’re going to turn failure into progress, you need four things:

Space to fail. Not every domain allows for this. You don’t get to fail at neurosurgery or skydiving. But most of what we do isn’t life-or-death, and we act like it is. We need to identify the areas where experimentation is possible, where the downside is manageable, and where failure is educational rather than catastrophic. This is where progress actually happens.

Recovery time. Failure is depleting. It takes a toll. If you’re going to metabolize it into progress rather than just endure it, you need time to process, reflect, and fine-tune. There’s a reason “creation” and “recreation” share a root. You can’t make progress if you’re perpetually depleted. But don’t confuse recovery with indefinite rumination. Process it, learn from it, move on.

Honest feedback. This is the hardest one. You need someone who will tell you the truth about what went wrong, as well as a culture that encourages feedback and risk-taking. The goal isn’t to punish you or make you feel better, but rather to help you see clearly. Most people can’t or won’t do this. They’ll either spare your feelings or pile on. Finding someone who can give you constructive, honest criticism allows failure to become useful information instead of just pain. You need this early on, while you can still change course.

Definite optimism. Have a plan that preempts failure. Work with failure, not against it. Understand what you’re building and what you’re fighting for. Understand that failure is part of the plan. Your job is to ensure that each failure teaches you something that brings you closer to achieving your goal.

Learn to Fail or Fail to Learn

I hope you fail more. I’m not saying that because I’m mean; I’m saying it because failure is the currency of progress. If you’re not failing enough, then you’re probably not taking enough action. Whether it’s a new job, a new relationship, or a new creative project, you’re going to mess up. Probably multiple times.

The question is whether you’ll fail in a way that makes you smaller and more defensive, or in a way that generates the raw material for growth. And whether you’ll fail fast enough to actually use what you learn.

Einstein’s insight wasn’t just about science. It was also about how learning works, how competence develops, and how anything worthwhile is built. You don’t succeed despite your failures. You succeed through them. Failures are the work. They’re not interruptions to progress—they are progress.

Most of us were taught to avoid failure at all costs, and to feel ashamed when we couldn’t avoid it. That’s backwards. What we need is the ability to recognize failure as a messy but necessary process of transitioning from incompetence to competence and from perplexity to clarity.

Because you’re already failing. We all are. The only question is whether you’re treating those failures as progress or as a reason to quit. Are you failing fast enough to learn what you need to before the cost becomes too high?

Here's another take on Learning -- from Life -- from Rachel Naomi Remen:

"On Learning:

Life offers its wisdom generously. Everything teaches. Not everyone learns.

Life asks of us the same thing we have been asked in every class: "Stay awake." "Pay attention."

But paying attention is no simple matter.

It requires us not to be distracted by expectations, past experiences, labels, and masks.

It asks that we not jump to early conclusions and that we remain open to surprise.”

Mind bending approach to projects and life. Through this lens, the whole psychology of failure and frustration changes for good. Everything is a teacher, we just have to figure out what is there to learn (or unlearn).