Attachment Styles: How Our Early Bonds Shape Adult Relationships

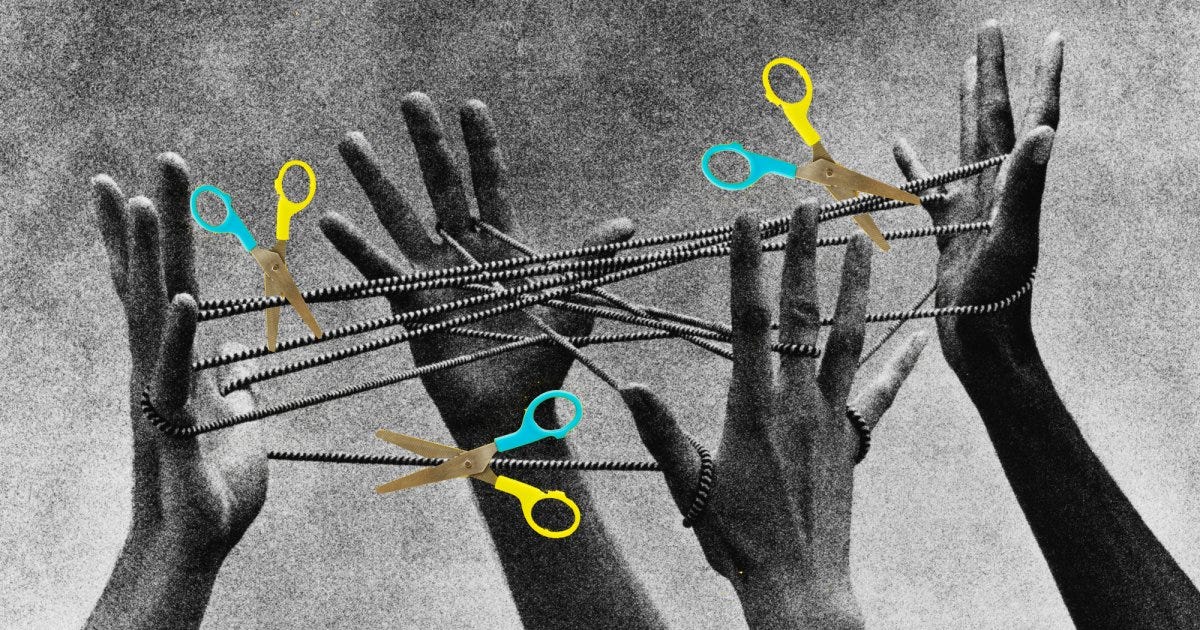

Our earliest relationships create the neural scaffolding upon which all future connections are built, shaping how we seek comfort, safety, and exploration throughout life.

I remember a patient—let's call her Emma—who burst into my office one morning, distressed after yet another relationship had imploded. "Why do I keep choosing partners who need constant reassurance?" she lamented. "It's exhausting, and I end up feeling smothered until I have to escape."

As a psychotherapist, I've witnessed this pattern countless times. Emma's predicament perfectly illustrates what Mary Ainsworth discovered in the 1970s with her groundbreaking "Strange Situation" experiments—how our early attachment experiences manifest in adult relationships, often without our conscious awareness.

The Strange Situation: A Window Into Our Relational Patterns

Ainsworth's elegant methodology involved observing how children aged 12-18 months responded when their mother briefly left the room and then returned. This deceptively simple scenario reveals profound truths about how we form bonds with others.

From an evolutionary standpoint, attachment is brilliantly adaptive. Humans are born remarkably helpless compared to other primates. Our extended dependency period necessitated a powerful biologically-mediated bonding system to ensure caregivers remained close and attentive.

But what makes Ainsworth's work so fascinating is how clearly it demonstrated that not all children respond the same way to separation and reunion—revealing distinct attachment patterns that persist into adulthood.

The Four Attachment Styles: A Neurobiological Dance

Secure Attachment (52% of the population)

Children with secure attachment show concern when their mother leaves, happiness upon her return, and, once reassured, comfortably return to exploring their environment. This beautiful balance between connection and exploration forms the foundation of emotional well-being.

Adults with secure attachment feel comfortable in close relationships. They trust both themselves and others, maintaining a healthy equilibrium between intimacy and independence. They've internalized the message: "I am worthy of care, and others can be relied upon."

This pattern develops when caregivers respond consistently and appropriately to a child's needs, creating what attachment theorists call a "secure base" from which to explore the world.

Avoidant Attachment (17% of the population)

Emma displayed classic avoidant attachment. As a child, she would have appeared indifferent when her mother left the room, often ignoring her upon return and focusing intently on toys instead of interaction—a precocious but defensive independence.

Adults with this pattern feel uncomfortable with emotional intimacy and strongly value self-reliance. They trust themselves but not others, having learned early that depending on others leads to disappointment.

This adaptation typically emerges when caregivers are emotionally unavailable or reject the child's bids for affection. The developing brain essentially "deactivates" attachment needs as a protective mechanism, learning to function without external emotional support.

Anxious-Ambivalent Attachment (11% of the population)

Children with this pattern show intense distress during separation and remain difficult to console upon reunion. They oscillate between seeking contact and rejecting it, too preoccupied with the relationship to explore their surroundings freely.

As adults, they constantly seek proximity and reassurance, fear abandonment, and may become "clingy" or excessively demanding in relationships. They doubt themselves while idealizing others.

The neurobiological basis is fascinating—their attachment system becomes "hyperactivated" due to inconsistent parental responses. Sometimes their needs were met, sometimes ignored, creating a brain perpetually vigilant for signs of rejection.

Disorganized Attachment (20% of the population)

The most concerning pattern shows contradictory, incoherent behaviors—approaching while looking away, freezing, or displaying fear toward the parent. These children fail to develop any coherent strategy for managing separation.

Adults with disorganized attachment often have chaotic relationships and difficulty regulating emotions. They display contradictory behaviors in relationships, simultaneously seeking and fearing closeness.

This pattern typically develops in response to traumatic experiences or frightening/maltreating parental behavior. The child faces an impossible dilemma: the person meant to provide safety becomes a source of fear, creating profound neurobiological confusion.

The Path to Earned Security

What gives meaning to my work is that these patterns aren't immutable. The brain remains plastic throughout life, and relationships themselves can be healing.

I worked with Emma for several months in weekly psychodynamic sessions as she developed awareness of her attachment patterns. We explored how her avoidance served as protection against vulnerability, how it originally developed as an adaptive response to emotional neglect, and how it now limited her capacity for intimacy.

Through the therapeutic relationship itself—a consistent, attuned connection—Emma began rewiring those early neural pathways. She learned to tolerate closeness without feeling subsumed, to communicate needs without shame, and to select partners capable of respecting boundaries while maintaining connection.

This journey toward what we call "earned secure attachment" isn't simple or linear. It requires courage to confront protective patterns that once served essential functions. Yet I've witnessed countless patients undertake this journey successfully through psychotherapy—particularly psychodynamic and attachment-focused approaches.

Recognizing Your Own Patterns

Self-awareness is the first step toward transformation. Consider reflecting on your own attachment tendencies:

Do you maintain a healthy balance between closeness and independence, trusting both yourself and others? (Secure) Do you minimize emotional needs and prioritize self-reliance above connection? (Avoidant) Do you seek constant reassurance and worry excessively about abandonment? (Anxious-Ambivalent) Do you experience chaotic relationships with contradictory approaches to intimacy? (Disorganized)

Remember that these patterns developed for good reason—they helped you navigate your early relational environment. Approach them with curiosity rather than judgment, just as you might study an interesting specimen under a microscope.

After all, we're all primates doing our best to navigate the complex social landscapes our brains evolved to inhabit, carrying attachment histories that influence us in ways both obvious and subtle.

And that, perhaps, is the most human thing about us.